Tuesday 29 May 2018

Thursday 24 May 2018

Chikugo

In 2002 I went to Japan for the first

time and stayed for a year in a small city called Chikugo. It was inaka, a rural place. There wasn’t much

to it beyond the main drag which led north towards Kurume and Fukuoka. It did,

however, have a train station, outside which there was a statue of a dog.

On the narrow road that led from the

station to my apartment someone had a rooster. It would crow loudly when the

sun rose, waking me up early every morning except on Sundays, when I typically

got home at about 7.30 after a long night out. There was also a high school

baseball ground next to my building, where the team would practice or have

games on weekend mornings. I was therefore routinely roused by the metallic

clink of hitters smacking the ball during batting practice, or by teenage

players calling out during fielding drills. I liked to lie on my bed with the

French window open, and feel the cooling wind blow in.

I worked as an English teacher in state

schools. I guess most foreigners doing the same job around Japan wanted to live

in Tokyo or Kyoto, but I had requested an assignment in Kyushu, the

southernmost of Japan’s four big islands, as I’d read that the people were

notably friendly and enjoyed drinking. The former statement was true,

especially in relation to my later experiences in Tokyo. I once made a friend

simply by standing outside 7-11. As for the part about drinking, that was also

accurate. When my Japanese colleagues and I went on a trip to the frozen north,

middle aged women were guzzling beers at 8.30 in the morning.

In the summer it was hot and very

humid. I would play football with my students during lunch breaks, after which

I didn’t stop perspiring for at least half an hour. Female staff would fan me

down before classes resumed, saying ‘Daijoubu?’

(Are you OK?), or set up the electric fan in front of me. I have a picture in

which I’m shaking hands with a boy after lunch, my t-shirt soaked in sweat. Still,

even though I was living in the hot south I never came across a cockroach or a

spider of any size. Those treats would come later, when I moved to the crowded

main island of Honshu. I did see the odd gecko, which liked to crawl along the

wall outside my front door.

In the winter my apartment, which was large by Japanese standards, was

bone-chillingly cold. There was no central heating, and for warmth I relied on

an air-conditioning unit and a kotatsu.

The latter is a low table with a heating device on the underside, along with a

duvet which you hide your body beneath. The Japanese love kotatsu, perhaps because they are accustomed to sitting on the

floor. For me, it was pretty uncomfortable, and my exposed head felt cold.

I loved some of the food I had in Kyushu. It was my introduction to

spicy Korean fare such as bibimbap

and yakiniku (barbecue). There were

excellent fast food restaurants nearby like Mos Burger and a curry place called

Coco Ichiban. Best of all, though, were the tonkatsu

restaurants, where you got a cutlet of pork deep fried in breadcrumbs until

it was kitsune-iro (fox colour),

along with a bowl of rice and as much shredded cabbage as you could eat. The

pork always came with a bowl of miso soup as well, but I never touched that. My

other favourite food was yakitori,

grilled skewers of meat, invariably accompanied by lots of beer.

I was unused to certain styles of

Japanese cuisine in those days, however, and had a sticky episode when my

colleagues took me out for a welcome dinner. It was a traditional meal, which

involved us sitting on tatami mats beneath a low table while a lot of suspicious

looking morsels were placed before us. After 5 minutes of sitting cross-legged,

I was in agony. One of the last dishes was squid, which was alive just a few

minutes prior to its appearance on the table. It was still twitching when they

laid it out and I, as the guest of honour, was given the first taste. It was

distinctly crunchy, and not at all pleasant.

From Chikugo it took about thirty five

minutes to reach the metropolis of Fukuoka. My Canadian friend and I frequented

gaijin bars and clubs whose diverse

clientele included American sailors from the base at Sasebo and young Japanese dressed

like black rappers, who sought to mimic the speech of their idols as well as

dressing like them. I used to drink Long Island Iced Tea poured from plastic jugs,

which led to fearsome hangovers the next morning. The biggest problem was

getting home, for the first express train used to leave at 6.57 in the morning.

By that stage I could barely keep my eyes open, and I fell asleep several

times. Once, I woke up just before Yatsushiro, which was about two hours beyond

my stop!

I never returned to Chikugo, although

I spent more than two years in Japan in the years that followed. I suppose it

has nothing to offer the visitor, even if it does now have a bullet train

station! For me, though, it was a wonderful place to spend a year when I was

twenty five.

Monday 21 May 2018

The Plaza de España, Seville

The first sound

that catches my ear is of castanets being shaken by a street vendor. Across

the square someone is playing Unchained Melody on panpipes, a song which seems

quite out of place in Seville. Then I notice the clip-clop of horses circumnavigating

the central fountain. All this overlays the low hum of tourists chatting to one

another.

We are in the

Plaza de España in Seville, one of the city’s less heralded sights. Indeed,

I’m sure when I first visited eleven years ago it had been essentially

forgotten. It is found beyond the old tobacco factory, at the end of an avenue

of lovely orange and plane trees, where parakeets chirp to each other and policemen

stand around stroking and feeding snacks to horses.

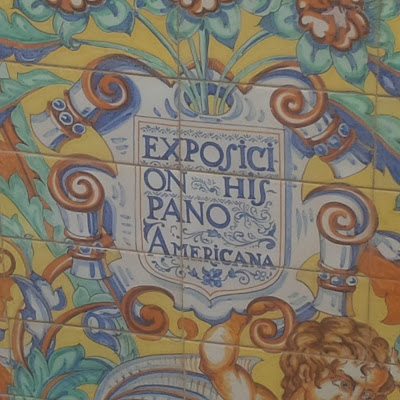

It was built for

the Ibero-Americana Exposition in the 1920s, and looks very striking. A long crescent

of columns stretches between two towers. The red and yellow flag of Spain flies

over the central building, and there’s a moat crossed by handsome single arch

bridges whose balustrades are painted blue and white. You can rent a boat and

row yourself along the water is you so desire.

What I like most

is the series of paintings that extends the length of the crescent. The predominant

colours are blue and yellow, and the images are painted on tiles. Each shows

some episode from Spanish history, such as Columbus departing for the New World

from Huelva and explaining his plans to the King in Salamanca.

Many of the

paintings are dedicated to scenes from the reconquest of Spain by the Catholic

Kings. They show the Christian army bivouacked below the dramatic cliffs of

Cuenca, and the surrender of the Muslims in Granada and Málaga. It crossed my mind that in politically

correct Britain these pictures might be controversial, arousing the ire of some

too-easily offended busybody.

We take our

leave of the square to the sound of Strangers in the Night being played on

panpipes.

Thursday 17 May 2018

The Bars of Seville

Seville is one of my favourite cities in the world. I recently spent

three nights there, and I could have stayed another week. There is something

wonderfully languorous about Seville, no doubt due to the intense sun and enervating

heat. The climate engulfs and eventually overwhelms you, so that you must

partake of that ritual of the south, the siesta. If a sleep doesn’t appeal, the

obvious alternative is to go to a bar. And there are a lot of bars.

My first experience of a

bar in Seville was not auspicious. The establishment in question, Bar Europa,

was rather empty when my uncle and I wandered in on a February evening and

ordered a couple of sherries. We were at the counter and I grabbed a stool, an

action which seemed to upset a local man nearby, so I offered it to him. He had

a weird and agitated manner, and didn’t seem mollified by my gesture. The bar

staff appeared determined to ignore this nuisance, and after quickly finishing

our drinks we left. Afterwards, I suggested to my uncle that the guy was looking

for a fight, although he was of the opinion that he was trying to make a move

on me!

That incident, which

occurred many years ago, came back to me during my recent stay. My travelling companion

and I visited a bar in the touristy Santa Cruz neighbourhood one evening. It was

busy with locals and foreigners and so loud that we had to stand outside in

order to have a conversation. We were nursing a manzanilla and a white wine and

enjoying the lovely evening weather, when a very drunk man put his sherry down

on our table. He said ‘Skol!’ and raised his glass vaguely in our direction. I

assumed he was Scandinavian on account of this greeting, but my friend rightly

marked him as a Spaniard.

The man raised his glass

a couple more times, as if acknowledging an invisible drinking buddy. I think

we were both filled with a sense of foreboding that he would, inevitably, try

to draw us into a conversation. And so it panned out. My cousin gamely made an effort

to respond to his questions, but it was gibberish. At one point we figured out that he was attempting to ask

us what we wanted to drink, but he was determined to ask it perfectly, and

fumbled around on his mobile for a couple of minutes before he found the

translation. When I told him I lived in Scotland his glazed eyes lit up and he

said ‘whisky!’ He shambled uneasily towards the bar to buy one for me, but the

bar staff sent him packing. Soon after, we took our leave. I’m sure the drunk

Spaniard has no recollection of ever meeting us.

Still, I think such

inebriates are a rarity in Seville. I have never seen anyone I would describe

as drunk in my favourite bar, Hijos de E. Morales, which is found on Calle

Garcia de Vinuesa, not far from the cathedral. Perhaps it’s to do with the

measurements. If you ask for a beer you get a caña, which is about 200ml in size, and the many varieties of sherry (fino,

manzanilla, oloroso, palo cortado and so on) are served in small glasses.

Morales is small and has only

a few tables, but most customers prefer to stand. Like the place in the Barrio

Santa Cruz, it attracts a mixed clientele of young and older Spaniards, as well

as tourists. You can order local specialities like garbanzas con espinacas (chickpeas

and spinach) and eat them while standing beside the wooden counter. Gruff and

ageing barmen look you firmly in the eye and bark out ‘dime’ or ‘digame’ (‘tell me’)

before taking your order. When they give you your change they slap the coins

down on the counter and slide them towards you. It’s loud, indeed another of

those bars where you may have to take your drinks outside if you wish to hear

what your friend is saying, but the patrons are good-humoured.

Still, we could not

entirely escape the cliché of the British tourist, for on two occasions we

finished the night in an Irish pub, drinking enormous glasses of whisky. There

was football on big screens and sunburnt British women drinking rosé, and we

could almost have felt at home. But stopping on one of the bridges that crosses

the Guadalquivir river on the way to our hotel, we turned round and looked back at the

old centre of Seville, where we saw the awe-inspiring bulk of the Cathedral and

the majestic Giralda tower lit up against the night sky.

Wednesday 16 May 2018

Ecija

The

courtyard is bathed in brilliant sunshine and the brown and white bell tower looms

above me. There’s a man sweeping the floor and I tell him I want to climb to

the top. He leads me into the chapel, where the light is muted, and I catch a

glimpse of a huge and splendid gold altar. The caretaker takes me to a glass

table where images of Christ can be purchased. I just give him a 2 euro ‘donation’

for the privilege of ascending the 115 steps.

I quickly reach the

level of the bells, which are discoloured from the passage of hundreds

of years. It occurs to me that a deafening din might break out at

any moment, so I check my watch: it’s 10.15. I figure I have another fifteen

minutes before I need to worry about my eardrums being blasted out. Through the

arches I see low hills in three directions and a vast open plain to the north.

We came to Ecija from the west, from Seville, over a

flat and dry landscape where little grows, except the hardy olive tree. The

only notable settlement between the two is the striking hilltop town of

Carmona. After an hour or so Ecija came into view, its famous towers standing

out above the whitewashed buildings.

They call Ecija the sartenilla (frying pan) of Andalusia.

The English writer Laurie Lee described it as ‘a lake of sun, a reservoir of

heat’. On the early May afternoon that we arrived the temperature was in the

high twenties, and it was startlingly bright.

There is a soporific character to the

place. We arrived during the siesta and felt exhausted enough to have a lie

down ourselves. Then we ventured into the main square, the Plaza de España, and didn’t even make it all the way

across before stopping in a café. We stayed for an hour and a half, drinking

coke and beer and watching children run around while their mothers sat in the

shade and gossiped.

The next morning, in the tower, it is

cool, for a light breeze blows through the gaps, and the landing is in the

shade. The main sound is the chirruping of birds calling to one another,

although I hear the occasional human voice from the narrow streets. From far

away, the faint hum of traffic is audible, but is mostly drowned out by the

lyrical songs of the birds.

From my vantage point above the

church of San Juan Bautista I see brown and orange

towers all around. I had heard these edifices were decaying,

but they look spruce and magnificent. Best of all is the tower above

Santa Maria church, a majestic and ornate spire that recalls the Giralda in Seville.

A single bell

tolls from some unseen church, marking the half hour, followed a few seconds

later by another single chime. Then the nearby narrow tower above the church of

San Gil erupts in noise, the sound wonderfully resonant at this height. I stay

another fifteen minutes, my solitude uninterrupted by another soul.

As I leave the

courtyard I notice the caretaker staring at me and it occurs to me that perhaps Ecija

receives few tourists. Maybe the energy-sapping heat puts them off. It's worth it, though, just for that view from the tower.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)